City P.C. George H. Hutt, Police Poet, and the Issue of Horse Cruelty

Animal cruelty, Horses, Jack the Ripper, Jews, London, Poetry, Uncategorized, Victorian Period, Whitechapel Murders 7 Comments »|

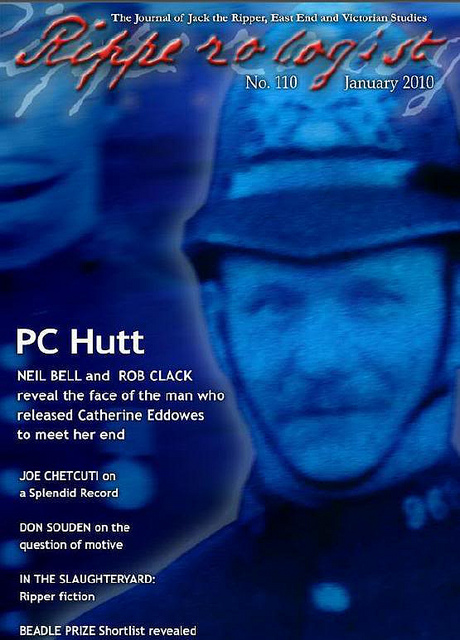

George H. Hutt, known as “The Police Poet” was the gaoler of Bishopsgate Police Station within the area patroled by the City of London Police. As such, in the early morning hours of 30 September 1888, he let the shortly to be fourth Jack the Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes out of gaol before she was murdered in Mitre Square, Aldgate. Hutt is known to have written numerous letters to the press, including one condemning the anti-semitism that grew out of the Ripper crimes, the East End of London at the time having a large immigrant Jewish population, and rumors circulated that the Ripper could have been a Jew. He appears to have been an unusually compassionate man with regard for the dignity of both human beings and animals. Hutt wrote a poem called “Saved by a Dog” about a dog who saved a woman cook’s life in Leeds in 1893 and another poem about the marriage of Princess Victoria Mary (May) of Teck and George, Duke of York (the future George V) that same year, for which he received an acknowledgement from the Royal family. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper

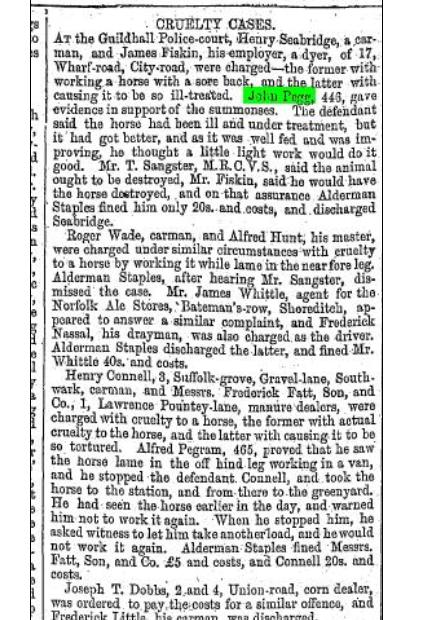

I recently came across another poem by P.C. Hutt which further shows the humaneness of the man: A HORSE’S LETTER to Ex-Police Constable 365 John Pegg Your life has been devoted to Before we had your kindly aid While drivers in their ignorance ‘Tis you and only such as you I’ve had the horrid toothache, Pegg, Again I’ve stood hour after hour Sometimes a drunkard held the reins, He loitered, tippling on the way, But dear old Pegg, you found it out, Now nearly thirty years you’ve been Ans though we are but helpless brutes, So horses, mules, and asses, too, May those who have the care of us George H. Hutt The poem references P.C. John Pegg, “Who, during his 29 years of service in the City of London Police Force obtained 1,300 Convictions for Cruelty to Horses, etc.” The “Sangster” that is mentioned is the veterinarian Thomas Sangster, M.R.C.V.S., who died on November 28, 1893. Following is an excerpt from an article on horse cruelty cases in which both Pegg and Sangster involved, as reported in the Illustrated Police News of September 23, 1882. . . .

It is conceivable that P.C. Hutt may have been partly inspired to write his “Horse’s Letter” by a similar literary effort by Reverend Dr. Thomas De Witt Talmage (1832–1902), the American Presbyterian preacher and social campaigner. For more on Rev. De Witt Talmage see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_De_Witt_Talmage Thus, it could be as with his poem about the hero dog in Leeds who saved the woman cook’s life, George Hutt was partly thinking of this earlier “Horse’s Letter” in composing his poem. Talmage’s composition also touches on the topic of cruelty to horses. A Horse’s Letter. My dear gentlemen and ladies,— I am aware that this is the first time a horse has ever taken upon himself to address any member of the human family. True, a second cousin of our household once addressed Balaam, but his voice for public speaking was so poor that he got unmercifully whacked, and never tried it again. We have endured in silence all the outrages of many thousands of years, but feel it now time to make remonstrance. Recent attentions have made us aware of our worth. During the epizootic epidemic, we had at our stables innumerable calls from doctors, and judges, and clergymen. Everybody asked about our health. Groomsmen bathed our throats, and sat up with us nights, and furnished us with pocket-handkerchiefs. For the first time in years we had quiet Sundays. We overheard a conversation that made us think that the commerce and the fashion of the world waited the news from the stable. Telegraphs announced our condition across the land and under the sea, and we came to believe that this world was originally made for the horse, and man for his groom. But things are going back again where they were. Yesterday I was driven fifteen miles, jerked in the mouth, struck on the back, watered when I was too warm, and instead of the six quarts of oats that my driver ordered for me, I got two. Last week I was driven to a wedding, and heard music, and quick feet, and laughter, that made the chandeliers rattle, while I stood unblanketed in the cold. Sometimes the doctor hires me, and I stand at twenty doors waiting for invalids to rehearse all their pains. Then the minister hires me, and I have to stay till Mrs Tittle-Tattle has time to tell the dominie all the disagreeable things of the parish. The other night, after our owner had gone home, and the ostlers were asleep, we held an indignation meeting in our livery-stable. “Old Sorrel” presided, and there was a long line of vice-presidents and secretaries, mottled bays, and dappled grays, and chestnuts, and Shetland, and Arabian ponies. “Charlie,” one of the old inhabitants of the stable, began a speech, amid great stamping on the part of the audience. But he soon broke down for lack of wind. For five years he had been suffering with the “heaves.” Then “Pompey,” a venerable nag, took his place, and though he had nothing to say, he held out his spavined leg, which dramatic posture excited the utmost enthusiasm of the audience. “Fanny Shetland,” the property of a lady, tried to damage the meeting by saying that horses had no wrongs. She said: “Just look at my embroidered blanket. I never go out when the weather is bad. Everybody who comes near pats me on the shoulder. What can be more beautiful than going out in a sunshiny afternoon to make an excursion through the park, amid the clatter of the hoofs of the stallions? I walk, or pace, or canter, or gallop, as I choose. Think of the beautiful life we lead, with the prospect, after our easy work is done, of going up and joining Elijah’s horses of fire.” Next I took the floor, and said that I was born in a warm, snug Pennsylvania barn; was on my father’s side, descended from Bucephalus; on my mother’s side, from a steed that Queen Elizabeth rode in a steeple-chase. My youth was passed in clover pastures, and under trusses of sweet-smelling hay. I flung my heels in glee at the farmer when he came to catch me. But on a dark day I was overdriven, and my joints stiffened, and my fortunes went down, and my whole family was sold. My brother, with head down and sprung in the knees, pulls the street-car. My sister makes her living on the towpath, hearing the canal boys swear. My aunt died of the epizootic. My uncle — blind, and afflicted, with the bots, the ring-bone, and the spring-halt — wanders about the common, trying to persuade someone to shoot him. And here I stand, old and sick, to cry out against the wrongs of horses — the saddles that gall, the spurs that prick, the snaffles that pinch, the loads that kill. At this, a vicious-looking nag, with mane half pulled out, and a “watch-eye,” and feet “interfering,” and a tail from which had been subtracted enough hair to make six “waterfalls,” squealed out the suggestion that it was time for a rebellion, and she moved that we take the field, and that all those that could kick should kick, and that all those that could bite should bite, and that all those who could bolt should bolt, and all those who could run away should run away; and that thus we fill the land with broken waggons, and smashed heads, and teach our oppressors that the day of retribution has come, and that our down-trodden race will no more be trifled with. When this resolution was put to the vote, not one said “Aye,” but all cried “Nay! nay!” and for the space of half an hour kept on neighing. Instead of this harsh measure, it was voted that, by the hand of Henry Bergh, President of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, I whould write this letter of remonstrance. My dear gentlemen and ladies, remember that we, like yourselves, have moods, and cannot always be frisky and cheerful. You do not slap your grandmother in the face because, this morning, she does not feel so well as usual; why then do you slash us? Before you pound us, ask whether we have been up late the night before, or had our meals at irregular hours, or whether our spirits have been depressed by being kicked by a drunken ostler. We have only about ten or twelve years in which to enjoy ourselves, and then we go out to be shot into nothingness. Take care of us while you may. Job’s horse was “clothed with thunder,” but all we ask is a plain blanket. When we are sick, put us in a horsepital. Do not strike us when we stumble or scare. Suppose you were in the harness and I were in the waggon, I had the whip and you the traces, what an ardent advocate you would be for kindness to the irrational creation! Do not let the blacksmith, drive the nail into the quick when he shoes me, or burn my fetlocks with a hot file. Do not mistake the “dead-eye” that nature put on my foreleg for a wart to be exterminated. Do not cut off my tail short in fly-time. Keep the North wind out of our stables. Care for us at some other time than during the epizoptics, so that we may see your kindness is not selfish. My dear friends, our interests are mutual. I am a silent partner in your business. Under my sound hoof is the diamond of national prosperity. Beyond my nostril the world’s progress may not go. With thrift, and wealth, and comfort, I daily race neck and neck. Be kind to me, if you want me to be useful to you. And near be the day when the red horse of war shall be hocked and impotent, and the pale horse of death shall be hurled back on his haunches, but the white horse of peace, and joy, and triumph shall pass on, its rider with face like the sun, all nations following! Your most obedient, servant, Charley Bucephalus. Heartbreaking stuff! We can readily see how caring people at the time such as the policemen George Hutt and John Pegg could become disturbed at such mistreatment of horses, who literally carried the burden of the economic and social life of people in the late Victorian period. |

Recent Comments