RipperCon in Baltimore, April 7-8, 2018, with tours of Baltimore April 6 and 9!

Alfred Hitchcock, Baltimore, Civil War, Edgar Allan Poe, Ivor Novello, Jack the Ripper, Jews, London, Marie Belloc Lowndes, Mysteries, Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Lodger, True crime, Victorian Period, Whitechapel Murders, silent motion pictures, stage and screen No Comments »|

If you are interested in Jack the Ripper, the Whitechapel Murders, Edgar Allan Poe, Sherlock Holmes, Victorian mysteries, or True Crime, this is the event for you. Baltimore is going to be a happening place on the weekend of April 7-8! Registration is $140 or $120 if you agree to wear period clothing. Price includes talks and panels Saturday and Sunday in the Main Building at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) 9 am to 5 pm including lunch and refreshments, Friday afternoon free walking tour of downtown Baltimore and evening reception at the Lord Baltimore Hotel. To book a place, $80 is due now and the remainder by or on Valentine’s Day, February 14 (RipperCon 2018 is for lovers!!!). Pay via PayPal to editorctrip@yahoo.com. Note that Saturday night banquet with speakers and entertainment and the Monday all- day Bus Tour are priced separately. Space is limited to 50 people so book early! RipperCon 2018 Speakers Circa 13-14 speakers are expected to give talks over the weekend. Look out for surprise announcements here as well as on Facebook & Twitter!

Carla E. Anderton “There’s Something About Mary: Whitechapel’s Darkest Night, November 9, 1888” Carla E. Anderton has long been fascinated by history and the human condition, particularly English history in the Tudor and Victorian eras. A speaker at the 2011 conference at Drexel University on “Jack the Ripper Through A Wider Lens,” Anderton made the elusive killer the focus of her debut novel, The Heart Absent (New Libri Press, 2013). Anderton has a Master of Fine Arts in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University and a Bachelor of Arts in English from California University of Pennsylvania. In addition to writing historical fiction, Anderton has published poetry, essays, articles, and plays, and has an extensive background in small press journalism. Currently, Anderton is the Editor-in-Chief of Pennsylvania Bridges, a regional print and online magazine, and an adjunct professor of English and public speaking at Westmoreland County Community College. She lives in California, PA, with her husband, Eric, and two cats, River and Rozey.

Amy Branam Armiento Armiento is an associate professor of English and the coordinator of African-American Studies at Frostburg State University in Frostburg, Maryland. A native of Fort Wayne, Indiana, she completed her B.A. degree at St. Francis College in Fort Wayne. Armiento’s Master’s thesis, Literature and Killers: Three Novels as Motives for Murder, was the culmination of her studies at Ball State University. She earned her PhD in English at Marquette University, focusing her dissertation on Edgar Allan Poe. Currently, Armiento serves as Vice President of the international Poe Studies Association. When she is not teaching or conducting research, she enjoys the splendors of mountain Western Maryland with her husband, Frank, stepdaughter, Milana, and dogs, Smeg and Stella.

Bernard Beaulé Bernard Beaulé will tackle the thorny issue of controversial but colorful quack Dr. Francis Tumblety and his candidacy for having been a leading Jack the Ripper suspect since 1995. Does ”Dr. T” still remain a viable suspect? Born a French Canadian in the town of Havre Saint-Pierre on Quebec’s North Shore, Beaulé spent some ten years in his childhood in the United States where his father studied surgery. Although he has a college degree in Social Science focusing on empirical research and he also attended law school, he never claimed to be other than someone looking for the truth. Beaulé and his wife are these days resident for much of the year in Mérida, Mexico, 190 miles west of Cancún. He is working toward a Master’s degree in Mayan archeology. Known by colleagues as a trouble shooter, Bernard Beaulé’s career brought him constantly closer to what he aspired to become—a writer. From governmental papers, political speeches, and, years later, given his passion for gardening, a book on how to design and build water gardens (a French-Canadian best seller!), he now adventures himself in the historical fiction genre. His first novel, My Ripper Hunting Days, allowed him to blend in all the aspects that an author working with the past should consider to be his ground rules: rigor, integrity, endless self-challenging, and acceptance of peer review.

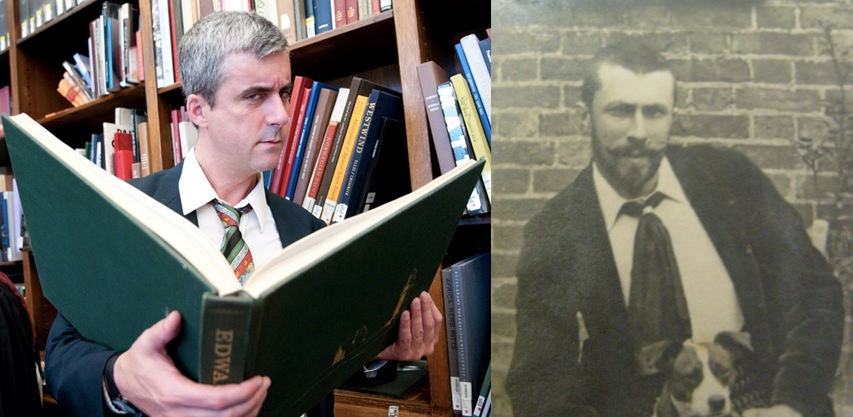

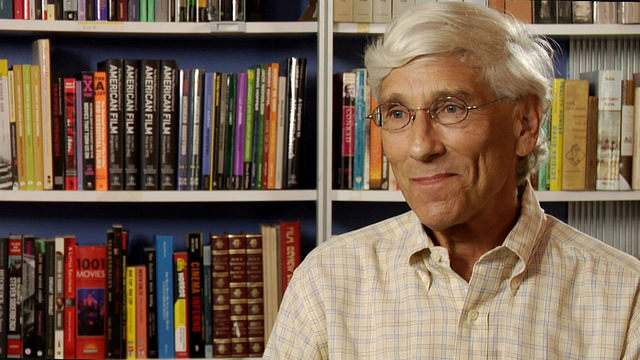

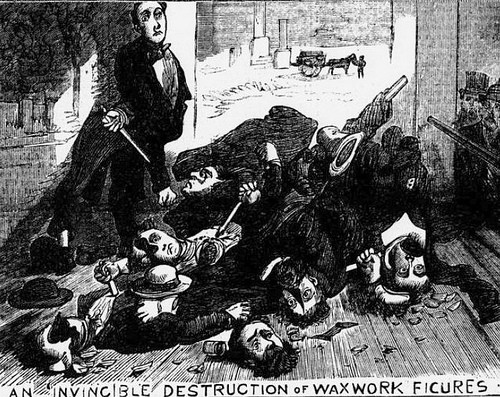

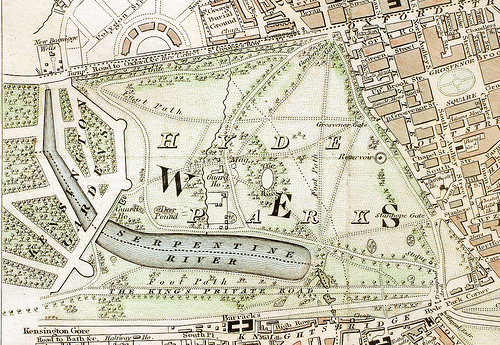

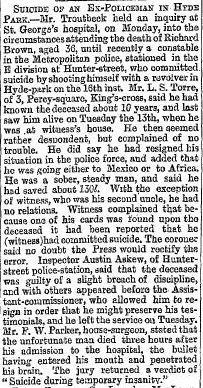

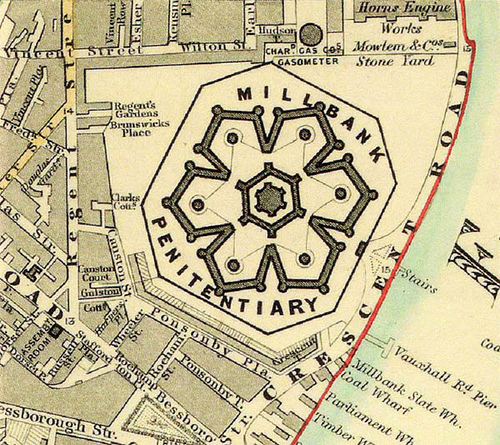

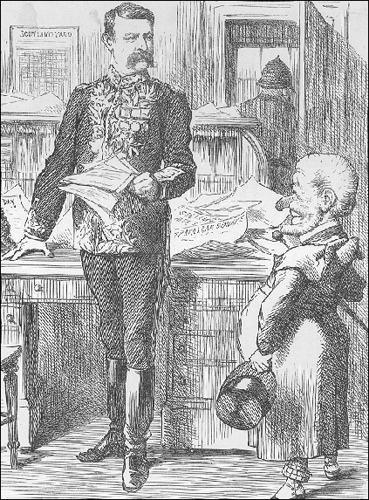

Mikita Brottman “A Morbid Curiosity: Murder in the Old Belvedere Hotel, Baltimore, 2006” Brottman will discuss the mysterious death of businessman Rey Rivera, 32, whose decomposing body was discovered a week after his disappearance in a closed meeting room. His injuries were consistent with the man having either jumped or been pushed from the roof of the Belvedere. Whether Rivera’s death was the result of suicide or murder has been the subject of much speculation and will be the subject of Brottman’s new book, A Morbid Curiosity. For more on the case see http://www.wbaltv.com/article/suicide-or-murder-evidence-reviewed/7054411. Brottman is a psychoanalyst and professor in the Department of Humanistic Studies at MICA. She is the author of Meat is Murder! (1998), a study of cannibalism in myth, crime, and film; and the true crime collection Thirteen Girls (2013). Her book, The Maximum Security Book Club: Reading Literature in a Men’s Prison, was published in June 2016 by HarperCollins and (see http://rippercon.com/rippercon-speakers-2016-18/www.mikitabrottman.com). She lives in the Old Belvedere Hotel. Christopher T. George “The Legend of Jack the Ripper” and “The Devil in Mr Deeming” Yes, the Whitechapel Murderer, otherwise known as Jack the Ripper, was a real-life serial killer who terrorized the East End of London in the autumn of 1888. Yet, human though he was, this unknown person has become much bigger than a living, breathing being. Veteran Ripperologist Chris George, a former editor at Ripper Notes and Ripperologist magazines, discusses the worldwide phenomenon of “Jack the Ripper” and also takes a crack at alleged Ripper Frederick Bailey Deeming, repeating his successful talk in his native Liverpool, England, in September on “The Devil in Mr Deeming.” In “The Legend of Jack the Ripper,” Chris will look at forerunners to the Whitechapel murderer, such as Spring-Heeled Jack and the London Monster and other sensations, and how word of the 1888 crimes spread to every corner of the globe, in an effort to understand why the spectre of the Whitechapel Murderer has both fascinated and frightened people for nearly 130 years. In addition, Chris will examine different candidates for the mantle of the Ripper and weighs their likelihood or non-likelihood to have been the infamous killer, in light of the existing information on the crimes. Sarah Beth Hopton “Mary Pearcey and the Hampstead Murders.” Hopton’s Woman at the Devil’s Door (Mango Books, 2017) about Mary Pearcey and her crimes in Victorian London is her first work of historic true crime. Her second book, Deadfall: Mountain Mysticism, Moonshine and Massacre in 1890s Virginia, is due out in 2019 from Indiana University Press. Among her past jobs, Hopton worked as a Florida crime and politics columnist for both The News Sun and [Closer magazine for a total of four years. She recently appeared on the Investigation Discovery (ID) channel special “Bloody Marys” to discuss Mary Pearcey, viewed by some as a possible “Jill the Ripper.” Hopton is currently an assistant professor in the English Department at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina. She lives on an off-grid permaculture farm with her partner, two dogs, many chickens, a few pigs, and four rascally goats. Chris Jones Chris Jones taught for 36 years in secondary schools in Liverpool, served for many years as Head of History in a Merseyside school, and later as Deputy Head Teacher at one of the city’s largest comprehensive schools. A few months ago, he retired from teaching and formed his own hiking company, Simply Trekking. He spent three weeks in September trekking up to Everest base camp. In 2007, Jones organised the Trial of James Maybrick at the Liverpool Cricket Club across the street from the former Maybrick mansion, Battlecrease House. Following the success of this event, he wrote the widely acclaimed book The Maybrick A to Z in which he tried to take an objective review of the evidence surrounding Florence Maybrick’s 1889 trial for the arsenic murder husband James and also James’ alleged links to the Ripper murders. He has continued his research into James and especially Florence, and has given talks on the Maybricks in both Britain and the United States, including in Florence’s home town of Mobile, Alabama. He has written several articles about the Maybrick case, most recently a critique of Bruce Robinson’s We All Love Jack, in which Robinson made certain doubtful claims with regard to the conduct of Florence’s trial. His current research is focused on the claims that the so-called Maybrick Diary was found by electricians working in Battlecrease House on March 9, 1992. *** For a week in August 1889, the eyes of the world were focused on a sensational trial in Liverpool. A young American, Florence Maybrick, was on trial for the murder of her much older husband, a respected city cotton trader, whom she allegedly killed by means of arsenic poisoning. Finally released from prison in 1904 (but never pardoned), she returned to the U.S. the following year, when she again dominated the front pages of major newspapers. In 1992, the supposed Diary of Jack the Ripper was “discovered” and overnight it turned James Maybrick into arguably the most controversial of all Ripper suspects. Not considered a suspect at the time of the Whitechapel murders and unmentioned in the famous Macnaghten Memorandum or any other contemporary police document, Maybrick was not linked to the killings until the emergence of the so-called Diary. His credibility as a Ripper suspect is therefore intrinsically bound up with the authenticity of this document—or the lack of it. In his talk, Jones will look at both Florence and James Maybrick. Was one a manipulative, clever murderer and was the other the most infamous serial killer of all time? Or, are both of them relatively ordinary individuals who have been unjustly accused of crimes they didn’t commit? He will examine the key moments in Florence’s trial and why the jury produced a guilty verdict. He will then address the big question—did Florence really kill James? Jones will then review the key arguments for and against James being a credible Ripper suspect. He will analyse the new evidence that has recently surfaced that arguably provides some much needed provenance for the Diary. Was James Maybrick really Jack the Ripper or instead an arsenic addict whose name has been cleverly woven into a forged document in an elaborate and clever hoax? Jackie Murphy “Jack the Ripper’s London” RipperCon M/C Jackie Murphy was born in North London, but brought up in Essex, 30 miles east of Whitechapel. She became interested in Jack the Ripper at age 13 when she was allowed to watch the six-part “Barlow and Watt” TV program about the case. She got further hooked on the case a few years later when she read Stephen Knight’s book. Then family life took over, but in the run up to the centenary of the case in 1988 the increase in books and documentaries really sparked her interest. In 1999, Murphy joined the Cloak and Dagger Club, now the Whitechapel Society, and has contributed to journals and books for the society, as well as other publications. She lives with her partner Alan Hunt in Dorchester, Dorset—Thomas Hardy country. Now a semi-retired teacher, Murphy works at the local history research center and makes quilts. Murphy tells us, “My ancestor was Benjamin Disraeli, or rather I am the result of his brother’s affair with the housekeeper! A more famous claim to fame is that my great, great grandfather owned Top Withins Farm, the basis for Wuthering Heights.” Brian W. Schoeneman Brian Schoeneman is an attorney, writer and veteran American political professional, with over fifteen years of government and private sector experience in government affairs. He has been studying the Whitechapel Murders since 1998, with an emphasis on the Metropolitan Police and Sir Charles Warren. He currently serves as political and legislative director for the Seafarers International Union, the largest maritime union in the United States. He has served in the past as Special Assistant and Senior Speechwriter to the U.S. Secretary of Labor, and former Secretary of the Fairfax County Electoral Board. In his capacity as Secretary of the Fairfax County Electoral Board, he garnered national attention for overseeing the closest election recount in Virginia history in 2013. Schoeneman is a graduate of the Catholic University of America’s Columbus School of Law, and receive a Masters degree in political management and Bachelor’s degree in political science from the George Washington University. He is a 2013 graduate of the University of Virginia’s Sorensen Institute for Political Leadership, where he was elected class leader by his peers. He is licensed to practice law in the Commonwealth of Virginia and is a member and former officer of John Blair Lodge #187, Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons of Virginia. In his community, he serves on the Vestry of historic St. John’s Church Lafayette Square, and on the Fairfax County Economic Advisory Commission. He ran for Virginia House of Delegates in 2011 and Fairfax County Board of Supervisors in 2015. He is the former editor-in-chief of BearingDrift.com, Virginia’s leading political website. Casey Smith Dorset-born W. J. Ibbett was a minor poet in an era noted for minor poetry. He was also a self-taught printer who produced badly printed copies of his poems. On some copies, the words were so poorly inked and broken that he used an ink pen to write over the printing to make it more legible. At times, it appears that the paper he used was taken from his day job at London’s General Post Office. Some of his poetry was produced as handwritten manuscript books, not because of a desire to create a beautiful book, but because it was cheap. However, Ibbett managed to get some of his books printed by a few notable private presses, and the famous typographic expert and Monotype Corporation publicity manager, Beatrice Warde was an admirer. Warde even wrote the preface to one of his collections of poetry. Ibbett’s friend and mentor, rare book collector Harry Buxton Forman actively promoted Ibbett. In the middle of the 20th century, Norman Colbeck, a London book dealer, systematically collected Ibbett’s works, most of which are exceedingly scarce. (A typical run of one of Ibbett’s books was less than 200 copies.) The third collector in this chain is Mark Samuels Lasner, one of the foremost collectors of late-Victorian art and poetry in the 21st century, and the person who initially got Casey Smith interested in Ibbett. Ibbett’s poetry, and life story, as detailed in his autobiography The Annals of a Nobody, reveal a complicated and troubled figure, a man who might have been responsible for the 1888 Whitechapel murders in Whitechapel, although Smith admits there is no definitive proof of this. However, Smith believes that bizarre and disturbing aspects of Ibbett’s life make him a good candidate for him having been Jack the Ripper. Casey Smith is a researcher, writer, and teacher based in Washington, D.C. He has a PhD in English Literature and Victorian Studies from Indiana University-Bloomington, where he concentrated on book history and material bibliography. From 1997 to 2014 he taught at the Corcoran College of Art + Design (later, from 2014-2016 at the Corcoran School of Arts and Design at The George Washington University). He has presented papers at academic conferences throughout the UK and US on the subject of Victorian book-culture and art. A former Vice-President of the Chesapeake Chapter of the American Printing History Association, he is now an independent scholar and Associate Professor Emeritus at George Washington University in the District of Columbia. David Sterritt “Red Riding, the Yorkshire Ripper on Film” Sterritt is a film professor at MICA and editor-in-chief of the Quarterly Review of Film and Video. In 2015, he completed ten years as chair of the National Society of Film Critics. His thirteen books include The Films of Alfred Hitchcock, published by Cambridge University Press in 1993, and he is on the Editorial Advisory Board of the Hitchcock Annual. His e-book on Hitchcock is due out this year. Charles Tumosa “A Policeman’s Lot Is Not a Happy One”

Tumosa lectures in the University of Baltimore (UB) School of Criminal Justice Forensic Studies program. Prior to joining UB, Tumosa supervised the Criminalistics Laboratory of the Philadelphia Police Dept. During his 18 years there, he worked on over 4,000 homicides and testified in more than 800 criminal cases. Tumosa also worked at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. During his time at the Smithsonian, Tumosa conducted analyses of artifacts including the Enola Gay, the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima; the Statue of Columbia on the dome of the U.S. Capitol; and a time capsule from evolutionary scientist Charles Darwin’s ship, the HMS Beagle. His research provided insights into areas such as conservation, anthropology and the mechanisms of ancient technology. For more on Tumosa see “The Art of Investigation: Painting a Picture of Applied Forensics” by Paula Novash (UB Magazine, Summer 2011). Janis Wilson “Could Sherlock Holmes Have Solved the Jack the Ripper Murders?”

Wilson was co-organizer for RipperCon 2016. She is a Baltimore-based Ripperologist and author of the novel Goulston Street, expected to be available shortly. A former newspaper reporter and trial lawyer, Wilson took the Ripper Tour in Whitechapel many years ago under the direction of Donald Rumbelow. The tour allowed her to appreciate how the world-famous slayer managed to repeatedly escape capture. After extensive study of the Ripper, she taught a course about the killer at Temple University in Philadelphia. In addition to her writing career, Wilson is a commentator on true crime for the Investigation Discovery Channel and has appeared in such programs as “Deadly Affairs” and the “Nightmare Next Door.” We look forward to welcoming you to Baltimore for what will be a great event, made even more special because it is taking place in the 130-year anniversary of the Whitechapel Murders. Don’t miss out on the only U.S. conference on Jack the Ripper in this very special year! Speakers for 2016 (including 2016 Podcasts)

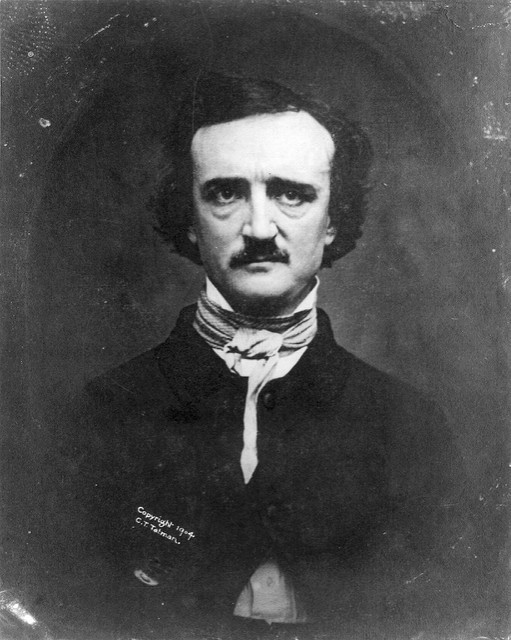

“Nutshell Studies” in Maryland Coroners’ Office. Space limited. Book soon. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849): The circumstances of his mysterious death in Baltimore in October 1849 have never been sufficiently explained. For complete information on RipperCon, go to http://rippercon.com/. DEADLINE TO REGISTER FEBRUARY 14! Don’t miss out on RipperCon in Baltimore in April 2018! |

.

.

visit to “

visit to “

Recent Comments